A Death at Jacobi

By VANESSA SWALES

The 19-year-old woman was a little past the full term of her pregnancy when she arrived at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx on the evening of March 26, 2015.

The plan was to induce labor using a common drug, Pitocin. She was healthy, and so was her soon-to-be-born daughter.

But the next morning, after the mother gave birth, a midwife noticed heavy bleeding from a deep tear in the mother’s vagina. A staff member estimated the mother lost about a pint and a half of blood — more than 10 percent of the blood in her body — but did not call for an immediate massive blood transfusion.

It was among several crucial mistakes, investigators would later determine. By 7:34 p.m.on March 27, the mother was pronounced dead.

The death was documented by state hospital inspectors who pieced together mistakes during those 23 hours at Jacobi. In a city with one of the most advanced hospital systems in the world, where nearly 120,000 babies a year are delivered, state inspectors have illuminated in harrowing detail the pain, suffering and tragic consequences when the birthing wings of New York City hospitals fail to live up to standards.

Reporters from the NYCity News Service reviewed public records between 2011 and 2017 and found several dozen violations involving childbirth in close to 20 hospitals across the city — a number that may be just a fraction of the actual violations, because many hospitals do not report complaints or do not report them correctly, according to the Association of Health Care Journalists. These include mothers inexplicably left unattended for long stretches of time, operated on without anesthetic, shuffled from one hospital to another during dangerous points of delivery and suffering from bad emergency care.

The inspection reports, maintained by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, offer a granular look into a growing pattern in New York State: Obstetrics, the branch of medicine involved in childbirth, was linked to the most deaths and serious injuries in the state, surpassing all other branches of medicine, even emergency room care, according to a report published last year.

Between 2014 and 2016, obstetrics was linked to 518 deaths and serious injuries statewide, according to data maintained in the New York Patient Occurrence Reporting and Tracking System (NYPORTS). Even worse, the number of those deaths and injuries rose 65 percent in the two-year period, from 131 in 2014 to 216 in 2016.

“Most of the events fall into the ‘serious injury’ category,” said Dr. Robert Ranzer, former chair of the NYPORTS advisory council for the state Department of Health. He said detailed investigations reveal most maternal injuries “are unpreventable, uncommon, severe complications — such as when there is an abnormality of the placenta leading to severe bleeding and further outcomes such as a hysterectomy to save the mother’s life.”

A spokeswoman for the state Department of Health said the increase may be the result of more accurate reporting and pointed out that Gov. Andrew Cuomo created a task force last year in an effort to reduce maternal mortality and racial disparities.

In March 2019, the Legislature passed a bill to establish maternal mortality review boards to develop strategies for reducing maternal deaths in the city and state. In a press release, a spokeswoman for State Sen. Gustavo Rivera noted that hemorrhages account for 16 percent of maternal deaths in the state.

One of those deaths linked to hemorrhaging involved the mother at Jacobi, who because of privacy rules was identified only as Patient Number 2, according to documentation from hospital inspectors.

Instead of rushing a blood transfusion when heavy bleeding began, the staff ordered packed red blood cells, a transfusion typical for lesser loss of blood.The hospital staff did not stop administering Pitocin, the drug triggering her contractions. They also had trouble finding the right vein for delivering the red blood cell transfusion.

When bleeding did not stop, staff decided to immediately deliver the baby girl with a cesarean section.

Less than an hour later, after the mother’s blood pressure had plunged below normal, a doctor finally called the hospital’s obstetric emergency team. At 11:33 a.m., they began a series of massive blood transfusions. She was rushed to an operating room.

The mother suffered a series of heart attacks and died that evening.

Inspectors noted that medical staff “failed to provide timely care.” The hospital staff underestimated the mother’s blood loss, and guidelines for such a postpartum hemorrhage “were not promptly implemented.”

The hospital staff communicated poorly with the mother’s family and pastor, according to the inspection report, and did not let the family see her until after she died.

Inspectors also found sloppy record keeping, including notations with the incorrect time on when the mother was transferred for surgery, a failure to document the cesarean section and an incorrect note on the time of death.

“We are committed to improvement of the care that we provide our patients through continuing education, safety training, and implementation of processes designed to limit morbidity,” said Robert de Luna, a spokesperson for New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, which operates Jacobi and the rest of the city’s public hospitals. He declined to comment on the inspection report.

Other inspection reports also flag poor standards of care provided to mothers during and after delivery.

At SUNY Downstate Medical Center’s University Hospital of Brooklyn, inspectors in 2011 found poor maintenance of hospital rooms, including cracked floors. They also documented that the labor and delivery isolation room, used to prevent spread of infectious disease, did not have negative air pressure for preventing airborne diseases spreading from room to room.

Inspectors confirmed a complaint by one mother who delivered a baby girl vaginally on July 15, 2011, but sustained a tear in her vagina. Hospital staff stitched her up, but did not use any anesthetic, a violation.

The hospital told inspectors that “appropriate actions and remediation has been taken with regard to the involved personnel.”

“The seriousness of the complaint was reviewed with the staff, and changes were made to ensure the importance of documentation of the care rendered,” said Dawn Skeete-Walker, spokeswoman for SUNY Downstate Medical Center’s University Hospital of Brooklyn.

At Mount Sinai Beth Israel, located in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, an eight-month pregnant woman came just before 2 a.m. on Dec. 13, 2016, complaining of heavy vaginal bleeding and abdominal cramps that started almost two hours earlier.

She had been making regular doctor visits, but had not felt well for a day, and believed she was suffering from food poisoning after bouts of nausea and vomiting.

Less than an hour later on that Tuesday morning, the attending physician and nurse reported the baby’s heartbeat was dangerously low. Within minutes, they sought to transfer her to Mount Sinai Brooklyn, which they felt could better handle her care.

More than 90 minutes passed before she would leave Mount Sinai Beth Israel. The hospital violated protocol by not re-checking the mother and the fetus, the inspector found.

At 4.20 a.m. she arrived at Mount Sinai Brooklyn.

Upon arrival, staff could not detect the baby’s heartbeat via sonogram. The mother had been diagnosed with placenta abruption, an uncommon, serious complication that could lead to a stillbirth. The inspection report does not state if the baby survived.

The physician who initially attended the mother defended the decision to transfer the mother to the other hospital. However, one staff member told inspectors that the decision could not be justified. There was also no documented effort to transfer the mother more quickly to a closer hospital to minimize the risk to the patient.

“The facility failed to effect a safe transfer to a receiving facility in proximity to the transferring hospital to minimize the risk to the health of the patient and her unborn child,” state inspectors wrote in the report. “This failure placed the patient and her unborn child at risk for harm.”

Mount Sinai Beth Israel did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A Death at Jacobi

Inspection reports reveal tragedies in city birthing wards. >>>

The Risks for Women of Color

Black women are 12 times more likely to die in childbirth than white women in New York City.>>>

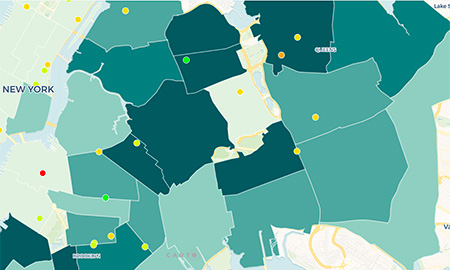

How Your Hospital Rates

Check the rates of C-sections and episiotomies at your NYC hospital.>>>

A student-powered service at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism

Reporters: Vanessa Swales, Irene Spezzamonte, Kaitlin Sullivan, Shaydanay Urbani

Faculty Advisers: Andrew Lehren, Benjamin Lesser, Christine McKenna, Ellen Tumposky

About the Team